A means to restore equal representation in the United States through the division of States

A frequent lament is that the design of the US constitution has created a system where voters are highly unequal. Most of all this is seen in the Senate, where the nearly 40 million residents in California have 2 seats in the Senate, and so do 550,000 in Wyoming. Indeed, if you take the 20 smallest states, they have fewer people together than California and get 40 seats in the Senate compared to the two. That same fact also means a smaller but real bias in the electoral college, with the smaller states having a bit more say in how the President is picked, though not with the extreme inequality in the Senate.

People lament this all the time, but it's only just lamenting. No plan described can happen while the GOP opposes it. Except these ones.

Two plans are outlined. One actually fixes the problem in a fair way but requires a great deal of sacrifice and change. The other is more doable, but it involves using a more extreme (and unfair) similar technique to force the GOP to the table to accept constitutional amendments to properly solve the problems that they would never otherwise accept, but might because they would face oblivion.

They both depend on this key option: The constitution fully permits dividing a state like California into smaller states, so long as this gets the approval of congress and the state to be divided. There are multiple precedents, and the approval of the President is not needed, though it would presumably be granted.

None of this would likely happen if not for the fact that they could be necessary to prevent a planned coup d'état involving abuse of the electoral college in 2024.

The Simple Brinksmanship Plan

The Democrats and the state of California prepare a plan to split California into a very large number of states -- perhaps 52 the size of a congressional district, or even 68 just larger than Wyoming. No minimum size is specified in the constitution or history, though if Wyoming can be a state, so can anything larger. In that extreme outcome, the divided states of old California would have 68 house members, 204 electoral votes and 136 Senators. About 80% would be Democratic, and 20% Republican.

The result would be almost total dominance of the Senate and Electoral College/White House by Democrats for some time, with a decent shot at dominance of the House. While an interstate compact could be done to lessen many of the effects on California, it would be a seismic change to the state that nobody really wants (least of all its 2 Senators who must approve it) but it's better than the alternative of a broken country.

Ideally, rather than having to do it, it brings the GOP to the table for a negotiated, semi-bipartisan repair of the imbalances in the system, though with the Democrats holding a nuclear weapon and the Republicans a nightstick. Those might include a national popular vote for President, the end of Gerrymandering and voter suppression, and a new body with proportional representation supplanting the Senate in power. (The Senate can't be changed, though its powers can be moved.)

A move this dramatic would not normally be attempted. However, the elimination of the Electoral College would effectively neuter any efforts by supporters of Donald Trump to carry out a coup by manipulating slates of electors at the state level. Such an effort would ruin the United States just by being attempted, whether it succeeds or fails. It must be nipped in the bud.

History and reasoning behind all of these actions follows below. There is also more on the simple plan at the end of this article.

Plan B

If the GOP refuse to pass the new constitution, another alternative exists which the Democrats can do on their own. They can offer to let all states which wish it to split into average sized states for a similar result, with less pain to the states.

Executive summary: It may be possible to undo these inequalities via extreme constitutional measures, without needing GOP agreement:

Working with congress, the larger states divide themselves up into multiple smaller states, so that all the resulting states ( from 84 to 435) are closer to even in population.

The sets of divided sub-states form an immediate interstate compact to work together to stay as close as possible to acting as their former single state, other than for federal election purposes. For the citizen, there is minimal effect from the fact that their state has been divided.

In addition to balancing the inequality of voters in the Senate and Electoral College It may also be possible to eliminate most Gerrymandering and voter suppression, and repair other electoral flaws.

The Senate jumps greatly in size, changing its character unless other measures can be taken. Senators pay a price to their careers.

The method involves unusual use of the Constitution but complies with its rules, though there are arguments both ways on whether it complies with its intent. It goes beyond "Constitutional Hardball" into the realm of a fist-fight, and one more extreme variant of it could be viewed as it becoming a knife fight. The approach is open only to the Democrats, but they are the ones who presently suffer under the inequality described above, but it is a costly approach -- so costly that even as much as they want to fix the inequality, they will probably shy from it. With the unprecedented attempt at an insurrection promoted by Donald Trump and enabled by many GOP lawmakers, this change has become necessary. Indeed, it is one of the few defenses against a 2nd coup attempt in 2024.

If you think doing this would be near-impossible, you're probably right. Only fear of a Trump coup might bring it about, and even that may not be enough (until too late.) Any of the techniques here might be useful not to do, but to credibly threaten to do. The threat must be real, even though it is costly, but it could be enough to bring people to the table. There was a time, not that long ago, when there was bipartisanship and cooperation and no risk of a coup -- perhaps a strong weapon could restore those times.

The Democrats control this tool for a good reason -- they have more voters than the Republicans, at present. That is normal, because in a two-party system, as parties vie for power, if one group gets a slight advantage due to the rules, the other group has to become larger in order to make it an even fight again. But there are elements of the system that do not have this bias, which could be invoked in an emergency, if things go too far out of whack.

Note again: This only gives an advantage to the Democrats if they get more voters. In a 50-50 national vote split, these approaches actually still slightly favor the GOP for both the WH and control the Senate, though the addition of DC and Puerto Rico as states would switch to slightly favoring the Democrats.

Recent polls suggest the Republicans are actually matching the Democrats in total popular support. If so, this plan does not prevent a Trump coup, and in fact it's not a coup any more, as he would win by all reasonable measures if he gets that much support.

This is possible only because the Democrats control the Senate, White House and HR for a short time. And they barely control it -- any action requires complete 100% unanimity of the 48 Democratic Senators and 2 independents, and near unanimity of the Democratic caucus in the HR. Which may make it a non-starter, considering how willing red-state Senators Manchin and Sinema have been to unify. Based on historical trends, this triple-control will almostl certainly end in January of 2023.

Why we got here

When the USA was founded, they knew they were granting unequal representation. In order to get all the colonies to join the union, they had to deal with the fact that some states -- smaller states and slave states -- feared they could get overwhelmed by the larger states. Some colonies would not join unless they were given a guarantee of extra power to protect themselves. It was deliberate. So deliberate that not only was each state given equal power in the Senate (and the corresponding votes in the electoral college) but this rule of equal franchise for states was made the thing that could not be changed by a constitutional amendment. That's right, even if 3/4 of the states wanted to fix the inequality of the Senate via an amendment, they could not, without permission from the small states who would lose that stature and thus are unlikely to grant it. It's the thing left that is so set in stone.

At the same time, while one might say "A deal's a deal," the reality is that the great-great grandchildren of everybody involved in that deal are long dead. That the descendants almost 250 years later might reasonably redo the deal to match the principles of the founders, who, after all, wrote that all (or at least all men) should be equal and that everybody deserved equal protection under the law, guaranteed by the constitution. Equality was their overriding value, and inequality was a temporary solution to a problem of their century. The former wins. Indeed, several of the founding fathers felt it was wrong to bind the people of the future to agreements by their dead ancestors, and even considered (but did not adopt) a formula to provide for that.

On top of that, today we take a different view of the fact that one of the reasons the colonies demanded special power remain within states was that some states, whose participation was necessary for the union, wanted to protect the ability to own other human beings. No deal with that as a significant purpose deserves our protection or devotion today. 80 years later it took war to undo the core of that part of the deal, but we don't need anything so nasty as that. They also didn't anticipate one state being 68 times larger than another, though Virginia was 10x Delaware (non-enslaved) at the time.

The constitution assures equal franchise in the Senate for states. It does not promise that states will always remain at the same size, or that new states would not be added, or even that existing states might be divided up into smaller states, as was done to split West Virginia and Virginia during the tumult of the war. (This division had very different reasons -- East Virginia wanted to secede from the US, West Virginia did not, but there is no question that a state can be formed from territory of another state if that state consented.)

When they wrote the constitution, they actually worried about the fact that as large new states were added to the west as equals, they would some day overwhelm the original 13. The draft constitution had a rule that new states had to enter the union on equal footing with the existing states, but that language was removed, due to that fear. Later, the Supreme Court made rulings effectively putting it back. Those rulings allow conditions to be put on a state joining the union, but once it becomes a state, it has the same full power of any other state to amend its constitution to remove those conditions within federal constitutional limits.

Division of the States

Put simply, I can see no impediment in the Constitution to the division of any state, in particular California, into some number of new equal states, as long as Congress and the state agree to it. (The President's agreement is not explicitly required in the constitution, though some argue that it de facto is.) There is not even strictly a limit as to how many states California might become. Long ago, a rule had suggested a new state be as large as the smallest state, which seems a reasonable rule, but it was removed. Applying that rule, California could become sixty-eight states, each larger than Wyoming! While many would argue against it, one can't make a population argument that the states are too small to exist, if Wyoming is not too small.

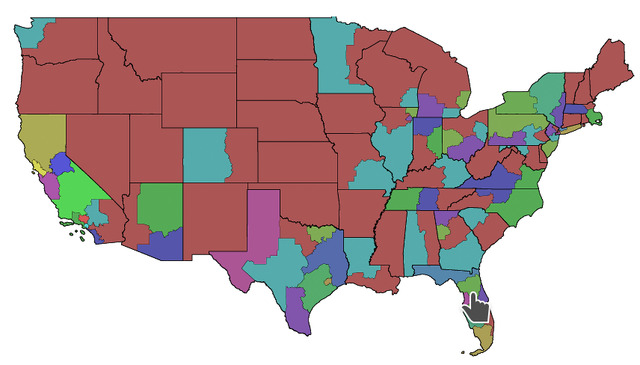

It’s hard to say what the right size for division might be. One approach would be to allow division to match the mean state size of 4.5M (6 districts) Under that example, California would become 9 states, Texas 6, NY 4, FL 5, IL, OH and PA 3, GA/NC/MI/NJ/VA/WA/AZ/MA 2 and the rest left intact. At the other end, it could be one state per district with CA becoming 52 states. Under present voting for the house, 42 of those are "blue" and just 11 "red" though several are "purple". The districts are almost contiguous, with eastern California being "red." At the same time, California has more Republicans than this might suggest and it possibly has more Republicans than any other state, but it also just has a lot more Democrats than any other state too.

Congress could make a non-partisan and equal offer to all states that they may elect to divide themselves if they meet certain conditions. The most basic condition would be that first they create division lines in a non-partisan and non-gerrymandered way. This might involve an emergency re-redistricting of states, allowed because they are brand new states. In the simple form of "one state per district" the districts would be redrawn with no gerrymandering first, then the division could then turn them into states. (Or there could be 2, 3, 4, or more districts per new state.) Note that ending gerrymandering is almost impossible unless one goes to proportional representation, but this is not possible for state borders. A set of borders done by an unbiased algorithm still results in a +26 district/state bias for the Republicans under current demographics, as calculated by 538. As such the right size of new states is worthy of a side-discussion.

The other simple condition would be that each sub-state clones the constitution of the original state, as amended to allow the division, with an equitable sharing of the non-geographic assets and debt of the original state.

A state would not be forced to divide. Any state that wished to retain its structure and even gerrymandered districts could elect to not participate. Or it could even be allowed that some districts remain bound together while all the others leave. However, if the state wants to keep equal power per capita with other states, it will be pressured to divide.

A Commonwealth Compact

Such a division would of course be an almost literally seismic event without something more. On its own, the consequences of such a division might be so great that people are unwilling to do them even to fix the inequality in the system and prevent a coup (and the subsequent possible destruction of the USA.)

As such, the states dividing themselves would make -- might even be required to make -- an interstate compact, enshrined in their root constitution, and blessed by Congress as required. This compact would attempt to tie together the new sub-states as much as possible under the constitution. In fact, the ideal compact would make the new commonwealth of states act in almost every way as one state, except for senate elections. The ideal compact would compel them all to maintain the same legal code, to elect the same person as simultaneous governor, and together to elect legislative bodies which pass laws which are identical in every state. They would keep unified taxes and have no barriers on borders. The federal government would, to the extent it can, agree to waive its rights to regulate interstate commerce within such a commonwealth.

It's also an option to have the compact continue to require each sub-state to vote its electoral votes according to the popular vote of the original state. This would happen due to the gamesmanship of the existing "winner take all" system, where if you unilaterally give up on winner-takes-all as a large state (as only small states Maine and Nebraska have done) you can sabotage your party's tally in a world where other states retain winner-takes-all. If California went on it's own to per-district electoral votes like Maine, it would sink the Democratic party in Presidential elections, so that party won't easily do that without matching offers from other states.

It is possibly not constitutional to create such a complete commonwealth. As such, it would end up limited by whatever the court said it could not do. But it would still do a lot, and lessen, if not mostly eliminate, any local negatives of the division. Of course, sub-states could, under their amending formula, decide to change this later and leave the compact if it suited them. So the division will never come without cost. Some of the divisions might be complete and permanent. The U.S. would be reformed.

Otherwise though, even the constitutions of the states would be amended in lock-step, through an all-commonwealth process similar to the one today.

Additional conditions

Congress could put additional conditions on getting permission to divide. There must be resistance to overburdening the offer with conditions, and so it should be limited to attempts to fix flaws in the democratic structure of the system, and not to attain any partisan goals. Some of the goals will appear partisan, in that one party likes or dislikes them because they currently gain or lose advantage, but ideally some basic principles can be upheld.

Just as the agreement would end gerrymandering, a broader rule could apply that no longer can elected officials have any sway over the rules by which they, or their affiliates (party members) are elected. Voting regulations, district boundaries and all other election procedures should be governed by non-partisans or unbiased algorithms. This is not easy, but it's a principle to aim for. It should address many questions of voter suppression or other efforts to bias elections to one party or candidate.

It would also be interesting to require superior voting systems, such as "Approval" multi-candidate voting, a simple system which allows minor parties to flourish without fear of vote-splitting. But that's about it. Prior to the division, people might propose other fixes but there should be a hard standard that they are truly fixes to flaws in the democracy itself. In particular they should be limited to rules governing elections and politics, not actual governance with a provable fairness. Rules of governance should be made and amended by the existing (or new) process.

The court may not permit every type of condition applied before admitting a state. In the past, it has allowed Congress to demand that Nebraska give votes to blacks, and that Utah prohibit bigamy before joining the union. The court however has suggested that attempts to regulate things which are not the business of the federal government may not do so well.

National Popular Vote

The full division of all states would make the Senate and College very close to equal in representation per voter. It is also possible to simply have the new states (of all types) all agree to participate in a different "popular vote compact," which compels them to vote their electoral votes according to the results of a newly created national popular vote. (There is no national popular vote in any election rules of the USA, that's an invention of the newspapers and not very accurate to boot.) There are already efforts to make such a compact, but because that proposed compact has 16 blue states in it and no red states, it has become partisan and unlikely to succeed. People debate if such a compact is constitutional, and you can read those arguments, but if we presume for a moment that it is, then this great division could make it come to be. (It is not necessary to get a majority of the electoral votes to join the compact, in fact it works with only a small fraction of them, because any election where the college and popular vote would differ is by definition a close election which would be swung to make them match with just perhaps 20% of the electoral votes.)

Even if there is no such compact to make a popular vote, the new electoral college could become closer to a popular vote than it is today, and even more so if Approval voting were adopted or winner-takes-all were forbidden in most states..

Some states might elect not to divide. They would be yielding power in the Senate and College. They might still join a popular vote compact to restore their power in the college to the same as all other states, though a typical compact would give them that for free anyway.

To be clear, if California, New York, New Jersey and Massachusetts elect to divide, it pretty much forces Texas, Tennessee and a few other red states to divide to maintain parity. If dividing requires joining a popular vote compact, it happens. To not counter-divide hands too much power to the Democrats.

The Huge Senate

The other big cost is it results in a much larger (870 seats in the extreme) Senate which is in effect a duplicate of the House. There a few ways to avoid that:

States could be divided into larger chunks, with 2 to 6 districts per state. The result would be less close to more full equality of voters, but might be close enough. In this case, the smaller states would not divide. The Senate would still grow to 150-300 members. At 3 districts per state, only the 28 largest states would get the offer to divide.

After everything is done, it's possible that even the states which didn't like the change might agree to make the Senate more manageable, and reduce it by constitutional amendment, ratified by 3/4 of the new states, to one Senator per new state. (Or even half a Senator per state, with each state pairing with another one to pick their joint Senator, presuming this still counted as equal franchise.) Indeed, faced with this radical approach, a whole bunch of new constitutional amendments to get a more sensible compromise might get on the table where today they are off it.

This change in the Senate is one of the other big barriers to this plan. To do it, all the Democratic Senators must sign on -- possibly unanimously in a 50-50 Senate. They would be signing on to a great reduction in their own importance. Instead of being one of 100 powerful figures, they would be one of 870 in the 1:1 case. They would have to put country and party before themselves, which politicians are not that good at doing -- and would have to do so unanimously. They would probably need some offer to sweeten the pot.

In the event of an amendment to 1 Senator per state, half the (almost entirely newly minted) Senators would need to end their careers, another hard sell. The long-established Senators would probably mostly survive.

It was the intention of the founders that the Senate be a more deliberative and slower changing body than the House, with longer terms and fewer members. The term-length remains, but absent an amendment, it is not possible to give equal Senatorial power per voter without increasing the number of Senators.

Uncertainties

It is unknown how courts would rule on many of the terms of such a division. It is likely that prior to such a division, if the Democratic party had the trifecta of White House, House and Senate, it could also do a temporary "court packing" by increasing the number of seats on the Supreme Court and appointing Justices unlikely to invalidate terms which match the primary goals of restoring voter equality and eliminating political manipulation of the election systems. Court packing is a controversial step, one likely to start an arms race when the other party next gets the trifecta, but it could be worth it to do this needed repair. After the repair was done, the court could actually be restored, as long as the remaining Justices would not reverse decisions on the repair process.

Even with this, because this does break the old deal, maybe no jurists, even ones picked for the job, would go along with all of it. That could be particularly true in the "knife-fight" version of the approach described later.

Some regions of states may not wish for the division, though it just requires the majority in the state government to happen. It might be good to let them have some choice on some matters.

Indeed, while this approach makes a future coup harder, there is a significant risk that some forces could be sold the idea that an effort like this is a sort of coup, which justifies a “counter” coup. This is not a coup at all, but it is a big change in the game, and might unseat those who might have won in the current imbalanced system, allowing them to view it as a coup. They might rise up against it in an insurrection.

At one-state-per-district, the District of Columbia would probably get statehood. Puerto Rico might become 4 states. At a larger ratio, DC might be too small to be a state by the new rules, unless it joined another small state that could not exist otherwise.

There is also some debate over whether congress can admit (or divide and admit) new states without the signature of the President. Past "enabling acts" prior to admission were passed as bills and signed by Presidents, and Congress has also sent proclamation bills to the President to sign, including with the admission of Hawai`i. But the constitution only requires the consent of Congress. President Andrew Johnson did a veto of the first enabling act demanding Nebraska give votes to black people -- Congress overrode him. At any rate, the current President is a Democrat and this would only happen with his moral consent, anyway.

An "1 Senator" amendment would require 3/4 of the new states -- 330 out of 440 -- to approve, but it is not partisan and simply makes the Senate easier to manage. Things still work without the amendment. Of course, there are many other things people would dream of putting in an amendment, but one should be cautious to assure they have bipartisan support. If enough states subdivided, there would be support for more complex terms, including an amendment fully entrenching the subdivision and interstate compact terms.

States could elect not to subdivide. While this would allow them to continue to gerrymander their districts to the extent their own rules and courts allow, to do so would be to trade a great deal of power in the Senate and Presidential elections for a slight advantage in their house delegation. For a large state to not participate would be a self-inflicted wound. The effect is strongest with 1 district per state. At 3 districts per state, states under 4M in population (23 of the current set) might elect to remain intact, and the 13 states with 1 or 2 districts would surely remain so.

The District of Columbia could become a state if it is 1 district per state. With larger sub-states, it might first amalgamate with Maryland, then re-divide if both entities wished this, or less likely but possibly with Virginia or even Delaware, but Delaware would be wiser just to keep small statehood. DC's state would be the most solidly Democratic-supporting in the union. Puerto Rico, which would deserve 4-5 districts (and thus states) might also be invited. Those states would also mostly support Democrats.

Since the inequality right now favors the Republicans, they would fight this very hard. They would consider their advantage on the playing field some sort of right, and feel violated. It could get quite nasty -- really nasty.

The parties re-adapt

After outlining all the costs, let me now point out that while making voting strength equal per voter is a noble goal, it won't cause nearly as much change as people imagine it would. That is even more true with a national popular vote removing the electoral college. In spite of all the umbrage, the few times the College and improperly added "popular vote" have differed, it's been by just a percent or two. That shift would be particularly minor, in particular because the parties would adapt. With a popular vote in place they would run 50 state races, which is both good and bad -- they pay attention to everybody but the races become even more expensive to manage.

But even though the Democrats would start with solid control of the Senate and House, it would not last that long.

In time, the parties would adapt to the new lines of support. Republicans would, by necessity to survive, alter their positions to attract enough new voters to become an equal political force again. Democrats would, oddly, help them by yielding voters to them who were never at the core of that party, to please other voting blocks within the party now that the brief luxury of power with fewer voters is available.

Within 5-10 years, the parties would become balanced again, though each modestly changed. However, from this point on the President would be selected by popular vote, or close to it, with each party trying to nominate somebody who can win, and the imbalance of power between smaller, less populated states and larger states would be eliminated, putting all voters on a roughly even footing. Again, voters should be clear that while this has been desired (particularly by Democrats) for many decades, the effect will probably be smaller than expected due to the ability of the parties to adapt, as they have throughout history, and as all other parties have adapted to demographic and power changes around the world.

Presidential campaigning would, as noted, become national and more expensive. Senatorial campaigning would become local and cheaper.

Ideally, what is proposed above is non-partisan, for it simply brings the USA closer to "one person one vote" to match its ideals. The problem is, any inequality flavors one party or another, and that party now wants to preserve the inequality even if it violates ideals. As such, these things -- like gerrymandering and unequal representation -- will persist unless fixed by methods such as this. I believe an action like this should serve only things that reflect ideals that are universal, even if partisan realities cloud that.

There is come concern regarding the Trump faction, which of course would be very opposed to this approach. However, because it temporarily locks the GOP out of power until it adapts, there is a danger the Trump faction could wield its power within the GOP during that realignment in a dangerous way. Today the Trump faction has control over many in the GOP because the GOP can’t win races without the Trump faction. Under this plan, they won’t be able to win many races even with them, but in time they could become the necessary factor agan, which is not good. The restoration of civility in the USA requires the end of the power of the Trump faction.

Is this cheating?

This does deviate from past political norms. You might call it a "loophole" but not if you believe that the long-term arc of the American ideal of democracy is one-person-one-vote. Even so, in the 20th century the USA was much more bipartisan. There was cooperation and compromise. The parties started to diverge, the population became more polarized, and the legacy inequalities in the constitution became more exploited -- this could be viewed as the greater abandonment of norms. This approach is an attempt to restore them. While it would strip the Republicans of the advantage they have gained through gerrymandering, voter suppression and the unequal population of states, these things were violations of the norms and principles of the USA or any modern democracy. Yes, many other democracies also have regional power which causes unequal power, also often for legacy reasons, but that hardly makes it good. If a political faction finds it can exploit a flaw in a democratic system, that's bad, but if it exploits that flaw to cement that flaw, as in Operation Redmap, something is needed to counter it. The President Trump has shown a willingness to abandon the norms which helped the country function at a staggering pace. It must be countered, not for a partisan reason, but to restore the functioning of the government. Once government functions, then the partisan issues should be fought out -- that's the purpose of the system.

The prior

biases (including those deliberately created by the Republicans)

contributed to the enabling of Trump and his insurrection.

Arguments that this doesn’t need to be done vanished with that

attack.

Deal's a deal?

It should be noted that the deal of the 18th century involved the 13 colonies. The 6 smaller colonies who gained extra power were New Jersey, Georgia, Connecticut, New Hampshire, Delaware and most of all the last holdout, Rhode Island. You will note that today, only 1 of those 6 are "red" and the other 5 might well agree to this restructuring even though their power would diminish. Indeed, the purple state of Georgia might surprise us, both because it’s purple and because it’s now much larger.. Kentucky, which was created by dividing Virginia not long after, probably would not. (It barely missed out on being an original state so was formed by division -- another precedent establishing the constitutionality of this process and alignment with founding principles.) A lot of the protection of small states’ rights was to please Rhode Island, which had threatened to return to English rule if it didn’t get what it wanted.

The Knife Fight

If the Democrats want to scare the Republicans even more, they can do more than just fix the inequalities.

As noted, there is no minimum size on new states. In a knife fight, they could have the states divide in a gerrymandered way. California could leave the 11 "red" districts in a single state, and divide the 42 blue districts not just into 59 Wyoming sized states, but 120 half-Wyoming size states. Or, if you want to stay at Wyoming size out of some otherwise abandoned sense of fairness, Massachusetts, New York, Puerto Rico could be divided in this gerrymandered way until the Democrats controlled 3/4 of the states. The red states could not be given the right to divide -- it's a knife fight after all.

With control of 3/4 of the states, they could call a constitutional convention (that needs just 2/3rds) and write as many amendments as they like without the participation of Congress or the President. And, if they were nearly unanimous, they could ratify any such amendment.

Complete and total power. Terrible, horrible power that nobody should ever get or have. If even thought about, the convention would be declared with a purpose, constraining what amendments it could write -- namely only to fix the inequalities. No partisan amendments about gun control, or abortions, or limiting Citizens United, or any other dream that belongs only to one party. Even then, it's probably too much power. Constitutional scholars actually differ on whether a constitutional convention can have constraints put on it during its creation. We have not had one since the original, so rules are not well established.

One advantage the convention could have is it could make everything much cleaner. It could not remove the equal franchise in the Senate, but it could possibly just remove all the power from the Senate and give it to another body, a proportional representation body. It could fully allow the old states to become one again, while still maintaining equal democratic power to all voters. The 100 original Senators could keep their importance. The supreme court could be restructured in a way to stop it from being partisan, with fixed terms so a new one is appointed every 4 years. There's a long list -- and almost anything is possible if it got support of 3/4 of the states -- either unanimous support among Democrats, or lesser support there but some support on the other side.

I wish I knew how to constrain this terrible power. Perhaps a plan would be to first have an old school amendment to clarify that a convention can be constrained, and then have the convention. It would be a way to help the Republicans feel not entirely left out, to not rise up in arms as some might if such a knife fight started -- turning it into a gun fight.

One option would be to do a few simple moves to restore equality, and then require any other amendments need the approval not of 3/4 of the states, but 3/4 of the people. So it was clear any amendments passed were not partisan. In theory. 3/4 of the states seems like a high bar but could be done with just over 3/8th of the people (51% of 3/4 of the states.) While unlikely, that's also a bug. Use the "knife-fight" only to make sure the rest of the "fight" is fair, with an equal voice for all. Fix only those things that have become partisan because they grant advantage, not because people disagree on issues.

Maybe, just maybe, if a convention existed just to restore fairness, a gun fight could be avoided. People who had a built-in advantage take a long time to accept that loss of that advantage is "fair." They take so long that wars have happened over that very problem. Several times.

So let's leave out the knife-fight for now, leave it as only a distant threat on the table. And fix the basic problems corrupting the system, let the parties adjust, and get back, some day, to being bipartisan or even multi-partisan.

The Coup Threat

This

document was first prepared in 2020 prior to the elections. Since

then we’ve seen the amateurish but scary insurrection of Jan 6, and more

chilling evidence of serious efforts at a coup. President Trump

attempted to convince legislators in Republican-run swing states to

certify their slates of electors in a manner different from the

results of the state’s popular vote. He was rebuked, but even the

aborted attempts were taken all the way to the count on Jan 6 and the

storming of the Capitol. Efforts are underway to make such

machinations easier, not harder. They could result in an even more

contentious result in Jan of 2025 if the result is otherwise close

enough to manipulate. The result could be a conflict so wrenching

that it destroys or severely damages the United States permanently.

If the fear of this becomes credible, radical action like this plan

becomes much more reasonable to discuss. If the electoral college

imbalance is corrected, then it becomes less likely (but not yet

impossible) that a clear winner of the national popular vote could

lose in the college, even with manipulation. However, the threat

of flipping very close swing states all in one direction could still

present a risk. That would call for some of the knife fight

techniques above if Trump actually won the college through improper

means in swing states in opposition to the will of the voters in

those states. It is only in that situation that they would be

justified.

Simpler plans (perhaps with better results.)

As these are both powerful tools, they may work simply as a threat. For example, the Democrats could prepare the bills for a division of states like these, and have all signatures in place, ready to pull the lever, then propose an alternative done by both parties that is a better choice for both.

It's "way" would be simply the actual repair needed to the constitution to have a national popular vote and to sideline the Senate with a proportional body, reducing its power. (The states-are-equal rule in the Senate can't be changed but the Senate could have its power greatly reduced to eliminate the effect of this. Though if all 50 states agreed, the Senate could be replaced entirely.)

The GOP would have to risk California doing this and taking complete control of the country for the Democrats. (While 20% of the new states would be "red" it's still enough. If not, unethical gerrymandering could remove most of those red sub-states -- as a temporary weapon, not a permanent solution.)

Particularly with an expanded SCOTUS, the GOP would have little choice but to come to the table and take a fair deal, or commit suicide just to force California to restructure its government. The deal would involve the ratification of appropriate amendments to fix the inequalities. There must be no partisan issues in the amendments, such as abortion. Those must be solved the traditional way, by the newly repaired constitution.

This approach overdoes the splitting (but not smaller than Wyoming so nobody can dispute the states are too small to exist) and involves no interstate compact or perhaps a simple one to remove all doubt that it's constitutional. The less the GOP thinks "we can get this ruled unconstitutional," the more credible the threat is. There is clear precedent for the splitting of states, and clear precedent for the Wyoming size, though a court could rule it's out of order by today's standards though it's not clear on what grounds.

As such, if a threat brings everybody to the table, then everything is on the table. It is no longer necessary to do the above plan which can be done without the GOP. In fact, if it took the division of California to force the GOP to the table, the resulting deal could undo that division, and bring every state back to normal, but without the problem of the Senate and College that come from that, which might be the best result.

Comments

Doug Deden

Thu, 2022-01-27 16:11

Permalink

generational math

You say "the reality is that the great-great-great-great [four 'greats'] grandchildren of everybody involved in that deal are all a century dead." That sounds like a fun math problem.

The youngest delegate to the Constitutional Convention was Jonathan Dayton, born in 1760. According to https://bloomlife.com/preg-u/advanced-maternal-age/, the average age at last birth ranged from 39 to 42 among US settlers between 1650 and the late 1800s. Let's be conservative and use 35.

So Mr. Dayton's youngest hypothetical child would statistically have been born in 1795, youngest grandchild in 1830, youngest great grandchild in 1865, youngest great-great grandchild in 1900, youngest great-great-great grandchild in 1935, and youngest great-great-great-great (four 'greats') grandchild in 1970. The average life expectancy (source: World Bank) in the US for people born in 1970 was about 70 years.

So, probabilistically, not only have these great-great-great-great grandchildren you speak of not been dead for a century, they will probably still be alive for another 18 years.

(It reminds me of the last Civil War widow, Helen Jackson. She didn't die until 2020. https://wgntv.com/news/last-civil-war-widow-dies-after-keeping-marriage-secret-most-of-her-life/ )

brad

Thu, 2022-01-27 16:38

Permalink

True enough

Though one would want to look at not the theoretical but actual maximum 6 generation chain in reality. The average generation is 31 years, so 6 generations is 186 years, born in 1946 so yes, I have overstated it. And there will be a few outliers at 5 generations so 4 might be better. The rhetorical point is the same but I do prefer to be accurate.

David Brown

Mon, 2022-01-31 06:00

Permalink

California

My first thought was this would not get through a filibuster, but a little research shows that the filibuster only applies to legislation, which this would not be. If Gavin Newsom were to spearhead adding 59 blue Wyoming size states he would likely be the next POTUS. Anyone have any thoughts on what that map would look like?

brad

Mon, 2022-01-31 13:51

Permalink

Next Potus

I have to admit I didn't think much of Newsom's ambitions as a reason for this. While he survived his recall easily it wasn't overwhelmingly.

The split into 68 (or whatever) state plan is a threat, ideally never carried out. And if carried out, it would be written so that it could be reversed by vote of the people of all the fragments of California, though the constitution doesn't explicitly talk about removal of a state from the Union.

As I see it goes:

Add new comment