V2V/V2I mandate may be dropped, the good and the bad

Submitted by brad on Thu, 2017-11-02 11:21Rumours are swirling that the US Federal government will drop the proposed mandate that all new cars include a DSRC radio to do vehicle to vehicle communications. Regular readers will know that I have been quite critical of this mandate and submitted commentary on it. Whether they listened to my commentary, or this is just a Trump administration deregulation, it's the right step.

Most of these issues revolve around fleets. Privately owned robocars will tend to have steering wheels and be usable as regular cars, and so only improve the situation. If they encounter unsafe roads, they will ask their passengers for guidance, or full driving. (However, in a few decades, their passengers may no longer be very capable at driving but the car will handle the hard parts and leave them just to provide video-game style directions.)

Most of these issues revolve around fleets. Privately owned robocars will tend to have steering wheels and be usable as regular cars, and so only improve the situation. If they encounter unsafe roads, they will ask their passengers for guidance, or full driving. (However, in a few decades, their passengers may no longer be very capable at driving but the car will handle the hard parts and leave them just to provide video-game style directions.)

Level zero is just the existing rider on horseback.

Level zero is just the existing rider on horseback. Level one is the traditional horse drawn carriage or coach, as has been used for many years.

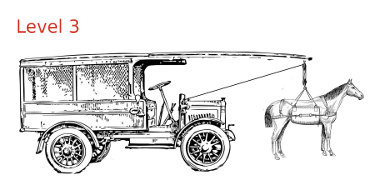

Level one is the traditional horse drawn carriage or coach, as has been used for many years. In a level 3 carriage, sometimes the horses will provide the power, but it is allowed to switch over entirely to the "motor," with the

horses stepping onto a platform or otherwise being raised to avoid working them. If the carriage approaches an area it can't handle, or the motor has problems,

the horses should be ready, with about 10-20 seconds notice, to step back on the ground and start pulling. In some systems the horse(s) can be in a hoist which can raise or lower them from the trail.

In a level 3 carriage, sometimes the horses will provide the power, but it is allowed to switch over entirely to the "motor," with the

horses stepping onto a platform or otherwise being raised to avoid working them. If the carriage approaches an area it can't handle, or the motor has problems,

the horses should be ready, with about 10-20 seconds notice, to step back on the ground and start pulling. In some systems the horse(s) can be in a hoist which can raise or lower them from the trail.

There are several things notable about Waymo's pilot:

There are several things notable about Waymo's pilot: